What Games Will Endure in the Ludic Century?

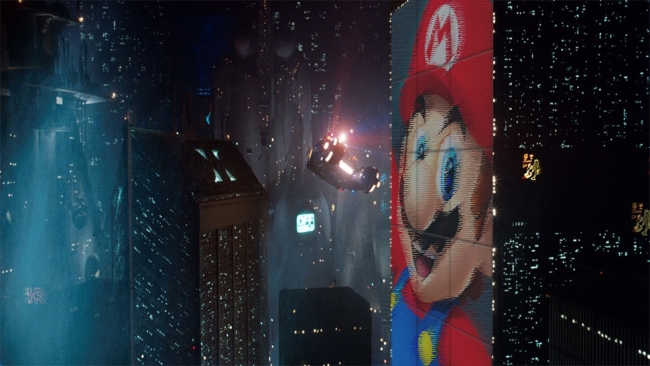

Haven’t you heard? The Ludic Century is upon us. As laid out in academic and game designer Eric Zimmerman’s “Manifesto for a Ludic Century,” the coming hundred years will be defined by interactivity, systems-based thinking and a focus on conscious design, where the 20th century was defined by information.

Yet only 13 years into this “ludic century,” where do we stand? If Zimmerman’s claim that the rise of digital games has brought the ancient form of structured play to the forefront of modern culture is true, what kind of ludic ambassadors are shepherding in this new era?

Since the rise of the iPhone and social games, traditional digital games have been thrown into a constant state of tumult. One way of looking at today’s landscape of games is to divide it into three categories: the indies, the business games, and the traditional digital games.

Indies are the small-scale titles created by teams of a few, propelled primarily by a love of games. Amid the monster success stories like Braid and Super Meat Boy are plenty of more modest successes, and a vast field of anonymous also-rans. Often, their primary goal is to make a great game with whatever resources available.

Business games are shrewd affairs run by corporate committees, with the aim of running and sustaining a business. They’re companies like Zynga, and individuals who attend events like last Tuesday’s New York Game Conference, with panels like “Maximizing Value & User Acquisition on Social Platforms” and “Social Casino Games: Winning Strategies”. Their primary goal is simple – to make money.

Traditional digital games come from the console era. What once resembled the indie developer environment is now a thriving business in its own right, with blockbuster titles requiring tens or even hundreds of millions of dollars to make. From their more modest origins to their overblown modern equivalents, these are what we recognized as games growing up – what mainstream digital games used to be. Due to the tremendous amount of money to be made, their goal is also to make money – but nowadays, these games achieve this by hitting a respectable quality bar.

These three groups may look like separate camps, complete with their own champions and detractors. But even in this early stage of a “ludic century,” there is room for all three.

For the indies: Games have made their way into our art and culture. Much as how Hip Hop took over modern culture for the past few decades only to recently cede ground to the EDM movement, games as a sense of identity has been steadily growing ever since they exploded as a novelty toy in the ‘80s.

For the business games: A niche of disposable commoditized games has emerged with the latest incarnation of smartphones. There is clearly a demand for low-priced digital distractions that has fueled a massive shift in the industry, due in no small part to the impulsive nature of buying a new iOS game to try – or better yet, taking a F2P game for a spin at no cost at all.

For the traditional games: Major releases have only increased their visibility as notable entertainment events. Midnight launches and marketing blitzes for Halo, Call of Duty, Borderlands and GTA sequels are only increasing the cultural significance of new game launches. GTA5’s record-stomping $800 million take on release day only reinforces the trend.

A Century Is a While

Despite all of this apparent momentum, a century is a long time. Years from now, when we have an American president who openly talks about his WoW guild days or boasts about his K/D ration in Call of Duty 19, which games will be looked upon as beloved classics?

Among the three strata of games categorized above, which will provide the games we look to for cultural guidance? Which games will students study in high school media classes?

The answer lies in the past. The works that truly stay with us through the ages – whether it’s the archetypal story of Frankenstein, the imagery and emotional devastation of Casablanca, the dialog of Shakespeare – they endure because they all tell indisputable truths about the human spirit, core truths that are not tied to specific cultural moments in time, despite the artifacts of the telling.

The downfall of man’s lust to conquer nature in Frankenstein; the search for ideals when the corruption of the world refuses to abide in Casablanca; the heartbreaking mistakes we all make when passionately moved for all the wrong reasons in Shakespeare – all are innate ingredients of the human experience.

The Trick of Games

What truths, then, do games tell? Not the stories that they tell, like the abortive attempt at weaving a relatable immigrant tale in GTA4, but in the gameplay itself. Playing as Niko, running around firing bazookas, stealing cars, shooting policemen – is there indisputable truth about the human spirit in there? Or is it just a meaningless leisure activity?

The answer is, don’t answer that. It’s a trick question because games are activities. They are not passive experiences like literature, film or theater. They are not linear media – they are activities like football, hacky sack, dinner parties, karaoke. They are like conversations.

It is this truth about games that opens us up to the real potential of the medium. In his critique of Zimmerman’s manifesto, game designer Ben Johnson suggests that the broadening influence of games could lead to an era of increased empathy for others, as games allow players to step into the shoes of others like no other experience can.

In any case, we have a long way to go before our ludic century is up. The games that will define the era more likely than not remain un-made, their creators probably decades away from being born.

But whatever form they take, and whoever makes them, it will be the games whose gameplay – whose activities themselves – convey an innately human truth that will be the games that endure through time.

All the rest will fade away.