The Hidden Bias Behind Faces

When you meet someone for the first time, a thousand things happen. Consciously and unconsciously you note their facial expressions, their body language, the tone of their voice – all of the myriad tiny movements that broadcast their essence as a person to you within seconds. It all happens so fast, and much of it below the conscious level, that we often fall back on logic to explain away why we feel a certain way about someone we’ve just met.

But beneath the pat comfort of logic, our beliefs are already formed. When meeting someone for the first time, our minds instantly scan through all of the faces held across our memories to check for a possible match, as a way to check if this person is someone you already know. If they don’t come up as a match, then you know this is a new person.

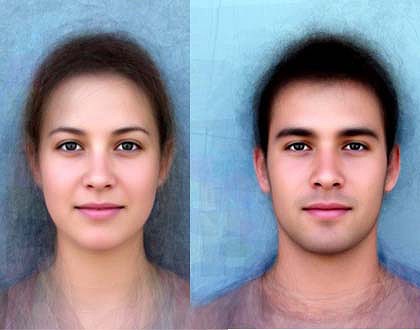

The curious thing is, remnants of that initial sweep get stuck in your mind even if the person is totally new. Maybe his chin or eyes remind you of the neighbor across the street from where you grew up. Maybe her stubby nose and wide cheekbones remind you of that girl in your health class in middle school.

Whatever the case, the older you get and the more people you encounter, the more likely you are to unconsciously map parts of faces from the past to new people. Because of how the mind works, the more features someone has in common with someone you’ve met previously, the more likely you are to inherit your opinion of that person when addressing the new one – even if their personalities couldn’t be more different.

These original faces, or personal archetypes that you’ve logged as the definitive carrier of these specific facial features, carry an outsize influence with how you interact with new people, subtly casting biases, prejudices and favoritism based solely on your personal connotations associated with their appearance.

Elusive Objectivity

In this light, influenced by artifacts from your past, true objectivity is impossible to attain – unless you are aware of the bias being applied and actively try to defuse the brunt of its effects. Only then, by becoming conscious of your innate distrust of or affinity for the new person, can you start to undo some of the subtle conditioning you’ve applied to yourself.

Yet on the other hand, what if predilection or distaste for certain features are more than just an informed opinion by someone who shares the same features? What if certain features – a particular shape of an eyebrow, an elongated or round-shaped face, high cheekbones, a certain shape of a smile – are aspects that resonate with you on a genetic level, inviting more justification via logic? In this case, the beliefs inherited to the new person would be valuable data indeed.

In any case, simply knowing that this background process of comparison and cherry-picking certain features exists makes the search for objectivity problematic. If our experiences are duly informed by all that we have seen that has gone before, and objectivity is truly a canard, then how do you live as a civilized individual in a modern culture? How do you make peace with your own biases and live life fairly, knowing that you are guaranteed to run into challenges like this through your travels?

The answer lies in mindfulness. Know that this profiling process is running in the background. Be aware when you find yourself giving preferable treatment to someone who doesn’t deserve it just because they elicit fond memories of some figure dear to you from the past.

Above all, ask yourself questions – tough questions – and never stop analyzing your behavior in the pursuit of a better way to be.