The Red Herring of Real-Life Landmarks

Making people care about things in games is hard. Not to say it’s impossible – but when most decisions boil down to ‘save the hostage’ or ‘restart the level,’ it doesn’t exactly fill the player with overwhelming empathy. So it makes sense that developers would constantly be on the hunt for ways to increase their game’s emotional resonance for the player.

Yet while there are plenty of ways to cultivate this feeling, one method – re-creating real-life locales in one-off missions specifically designed to elicit emotion from the player – tends to be leaned on as an option that’s so obviously effective, it’s non-debatable.

Unfortunately, this is hardly ever the case. In reality, by painstaking re-creating landmarks from real life in their games, developers run the risk of imposing superfluous constraints, needlessly sacrificing design integrity and investing massive effort for minimal payoff.

“You can get some emotional resonance from a real-life location, but that requires the location to already resonate.” –Andrew Grapsas

The topic of re-creating real environments in games came up in conversation with fellow developers Andrew Grapsas and Coray Seifert. While there is potential for iconic locations to mean something to the player, argued Grapsas, they require the player to be knowledgeable enough about them in the first place in order to carry any meaning.

This is why generic locations like airports, office buildings and parks can often be more resonant than unique, iconic locations, if only for the fact that in every case, there will simply be a greater chance that the player has been in a similar environment. Having that previous experience in a similar space allows for more opportunity to relate.

At the same time, opting to re-create an existing location locks you into the real-life restrictions for the space. Sure, there’s freedom to tweak the area to allow for additional gameplay spaces or different room configurations, but outside of small adjustments, you’re bound to reproducing the structure.

On the other hand, if you use a more generic location with architectural overtones of the target structure, you free yourself up to design a space that suits the gameplay above all.

“That’s why semi-generic spaces work well, like an airplane. We can all relate to being on an airplane.” –Andrew Grapsas

Yet even in the best-case scenario when you re-create a landmark that the player recognizes, any measure of resonance you achieve is dashed as the player quickly breaks the iconic structure down to its component parts in terms of gameplay.

The columns of the Parthenon become overlarge cover; the concourse at Grand Central Terminal becomes the sniper zone. Because the nature of gameplay demands that players evaluate their surroundings through a functional lens, the opportunity for emotional resonance is diluted as even the most elegant architecture is parsed into simple geometry.

Contrast this with the scene in Independence Day when the aliens blow up the White House. Since you’re watching the scene unfold purely as an observer, it carries much more weight. Conversely, if you were diving for cover and firing shots back at enemies while it happened, you would be far too busy to have the same reaction.

If the inclusion of real-life locations in games seems like a cheesy Hollywood tactic akin to hiring celebrity voice-overs and well-known screenwriters, it’s because they all share one glaring trait: a lack of authenticity to the game experience.

Of course, while all of these things can be used to great effect in games, if the motivation to use them is counter to the game’s purpose, the lack of authenticity will be obvious.

On the other hand, appropriating real-life environments can lead to great things – as long as the aim is to create an authentic game experience.

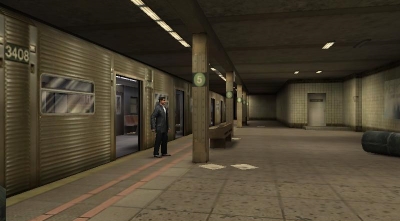

The Grand Theft Auto series is notorious for adapting real-world cities as the setting for their games, and it works so well because the decision to go with a specific locale pervades the entire game. The Miami of Vice City, New York of GTA4, and Los Angeles of San Andreas fully inform each game’s mechanics, characters, missions and sensibilities.

To drive the point home, Rockstar’s signature filter of cartoony parody combines with the stereotypes of each city we’ve all absorbed through a lifetime of media exposure to create something that feels handcrafted for each game’s specific purpose.

The same can be said for most games that are set entirely in a real-world counterpart, as opposed to a level or two. Sleeping Dogs, the True Crime series, the Assassin’s Creed series and the upcoming Watch Dogs all use their source material as a base layer before adding their distinctive gameplay.

Yet you don’t have to re-create an entire city to gain the benefits of real locations. There are vast possibilities in environmental storytelling, but they all require building meaning and context within the game first.

In an early scene in Bioshock Infinite, when Elizabeth opens a tear to Paris, we know that this is Paris because the Eiffel Tower looms in the background, clearly communicating that her ability allows her to open portals to other places. Far from an empty reference, this example shows the potential for effective real-world callbacks – as long as the game doesn’t rely on making references for their own sake.

No Shortcuts

Like most things worth doing, there are no shortcuts to achieving emotional resonance in the player. To do this right requires a conscious investment of the player’s time in order to build the necessary context for a meaningful payoff.

In the end, if given the choice between re-creating a major landmark or building your own space from the ground-up, it’s your call to decide which would lead to an experience best designed for the game’s specific mechanics, pacing and purpose – and not anything else.