In Search of Meditative Games

Fun in games is under attack. OK, maybe not under attack, but it’s definitely getting elbowed in the ribs. David Cage wants to see the industry using mature themes to deliver games with intent; Jane McGonigal wants to add 10 years to your life through play; and Frank Lantz, in his introduction at NYU’s Global Game Jam site in January, encouraged developers to instead focus on creating joy, stating that “fun is overrated.”

But there’s another intention that some games have been exploring off and on for years, something you can see glimpses of beneath the zoned-out zombie stare that comes from any hours-long play session: meditation.

Meditation at its core is an exercise in stillness, in quieting the mind to deeply reflect on life and your place in the world. The hope is that the repeated practice of focused introspection will help you to channel out the myriad distractions and manufactured dramas that seem to fill our lives. Unfortunately, for most of us, meditating like this is pretty boring.

Thankfully, there are other ways to meditate that, while maybe not as effective, are still better than not doing it at all. Engaging in fast, repetitive, physical activities like running, bicycling, skating or skiing can trigger a similar sense of reflection by essentially separating our physical selves from our mental processes. The repetitiveness of the activity allows your body to go on autopilot while your brain is free to work through the problems of your conscious (and unconscious) self. The separation is at once freeing, transcendent and kind of creepy (but in a neat way).

The usefulness of this kind of meditation cannot be overestimated in arriving at conclusions to tough problems. So why not create games that invoke just this kind of reaction? While a few titles try, and others accomplish it inadvertently, there seem to be three kinds of approaches developers take, with noticeably different results.

The Nothing Games: BYO Meditation

“This is not a game to be won. Play for experience. Walk and look. There is no goal. There is no story. Simply allow the atmosphere to embrace you. Do not think. Do not want. Just be.” –Bientôt l’été

The first kind of meditation game attempts to mirror the practice of traditional meditation by forcibly provoking deep introspection through the game mechanics and world. Games like Proteus send players into a sparse world with seemingly no objectives, with only the hinted-at goal to explore and quiet your mind. Tale of Tales’ Bientôt l’été begins its similarly sparse experience with a literal mandate to “just be,” even as the few beguiling constructs you encounter beg to be pondered, experimented with and progressed through.

Yet as interesting as some of these games may be, trying to force introspection through an environment is not too different from sitting on a different pillow when giving traditional meditation a shot. They don’t succeed well in creating meditative states because their meditative style, focused introspection, is foiled by what they actually are: active stimuli. Even if not much is happening in-game, the player can still navigate and explore, and the curiosity to see what’s next thwarts any sense of true reflection. Since the benefits of true meditation come by closing every source of stimuli, using this approach doesn’t usually meet with success.

The Focused Relaxers

Next is a class of games that uses more structure, but still maintains a relaxing pace designed to evoke reflection. These games can be objective-based, or have goals that are merely suggestions. Titles like Zen Bound, The Endless Forest, Flow, Flower and PixelJunk Eden place the player into relaxing environments with soothing music, and subtly guide them along missions that vary in open-endedness.

Stepping up from the first category, these games present options to the player in terms of possible actions and let them complete sections at their own pace with minimal intrusion. Yet while they do a better job of establishing a sense of flow, the slower pace keeps the player’s physical sense in line with their mental processes, creating more of a sense of serenity and relaxation than meditation and introspection.

The X-Treme Zen Machines

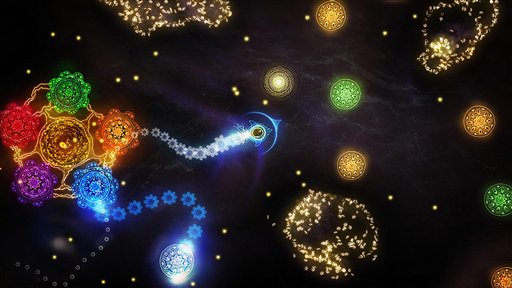

Lastly, there are the fast-paced Zen machines. These kinds of games couldn’t be more different from the previous two groups – they’re fast-paced, objective-focused, are usually linear and demand player concentration to prevent failure. Games like Frequency (and later Amplitude, Guitar Hero and Rock Band), Tetris, Dyad and Rez require a high level of motor skill proficiency to be successfully played.

While at first it might seem counter-intuitive to demand so much of someone in order to induce a meditative state, it’s actually the most natural thing. When you’re jogging in the park or pedaling in the middle of spin class, think of all the actions your body has to coordinate to make sure you don’t fall over or get swiped by a car – on a purely mechanical level, they’re not that different from the complex finger motions needed to play Rock Band with competency. Think about the faster settings you crank the treadmill up to when you’re literally hitting your stride – how different is that from slamming Tetris pieces into place when they’re falling at blinding speeds?

It’s these games, oddly enough, that mimic the sense of active meditation more than anything else.

Your Meditation May Vary

Of course, all of this is subjective and subject to change. Should VR hardware like the Oculus Rift fulfill its promise, perhaps walking around in a Proteus-like world could one day be a life-changing experience. Yet while slower-paced games can be relaxing, they don’t promote the same type of mind/body separation that highly structured, high-speed games do. For now, if the goal is to induce a waking meditative state, fast, physically-demanding game designs are necessary to shift the player’s subconsciousness into overdrive.