Mind Games: Offloading Cycles to the Player’s IPU (Imagination Processing Unit)

At first glance, computers and video games seem to be a perfect match. Computers allow games to have absurdly complex rule sets that nobody has to remember, they can create real-time simulations that would be impossible to do otherwise, and they allow us to play with other people all over the world.

Yet in some ways, computers are terrible for video games. In a Q&A at Game Horizons a few months back, Will Wright remarked on certain tasks that the computer is ill-suited for, citing Maxis’s decision to have the characters in The Sims speak in the gobbledygook Simlish language instead of English.

“For example, in The Sims, when you hear the people talk, you don’t actually hear them saying anything. You hear this kind of gibberish language. Through a lot of experiments, we determined that we could actually have them speaking in English or some other known language, but they very quickly became robotic and repetitive. On the other hand, if they speak gibberish, your mind naturally fills in the blanks and imagines a conversation… In essence, what we did is we offloaded that part of the simulation into the human imagination.” –Will Wright

Recently, Bioshock Infinite designer Tynan Sylvester elaborated on this concept of offloading elements of a computer game simulation into the player’s imagination in a masterful Gamasutra blog post. And while the idea is certainly compelling and the Sims example rings true, finding concrete ways to incorporate the main concept into games in development can be baffling. But by digging deep into the core problem, we can discover valuable ways to use the concept to strengthen our designs.

And all of these ways rely on maximizing the player’s IPU – or Imagination Processing Unit.

The IPU is the Gateway to Immersion

It’s the same reason the book is often better than the movie. With reading, the experience is a collaboration between the reader and the author. The author assigns specific things for the reader to simulate in their IPU, and the reader complies, helping craft a personalized experience that the reader can easily buy into.

Whereas with films, the entire screening time is a didactic experience of the filmmakers explicitly showing viewers what they want them to see. Sure, cinematic masters may infuse their movies with sublime beauty and intriguing scenes open to interpretation, but as a medium there is much less room to have a highly personalized experience.

Games, on the other hand, can be both. Game designers and creators lay out the world and the immutable plot points/mechanics, and then players are granted the freedom to live the moment-to-moment experience between those points. The degree of flexibility varies from game to game, but the virtue of having any kind of freedom is what makes games so special.

Using the IPU

The ideal solution here, if you’re intent on following Wright’s example, is to have the player fill in as much of their flexible in-between-predefined-points time with their own imagined meanings and implications.

While each game will call for different solutions, here are a few examples that have worked well in the past:

To start, look to content-heavy areas or gameplay sections that follow a formula as opportunities to offload to the IPU. In the case of The Sims, character dialog would have required reams of text written and localized for each territory the game was released in. By opting for the Simlish solution, all of this work was rendered unnecessary, saving hundreds of hours of development (at least).

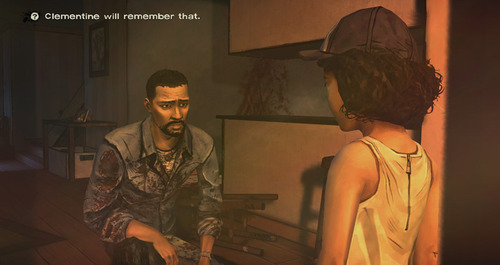

In the case of Telltale’s The Walking Dead, having conversations with characters is a solid pillar of the game’s design, and so it follows that conversations are a largely formulaic part of the game. By adding a simple “[Character] will remember that” message at the end of every conversation, players internalized the idea that each character they spoke to would bring all of their previous conversations and baggage with them throughout the game, even if a character only had one dialog scene before meeting an early death. Doing this made each character feel more real, since you could easily imagine them carrying their life experiences with them into future dialogs – just like real people do.

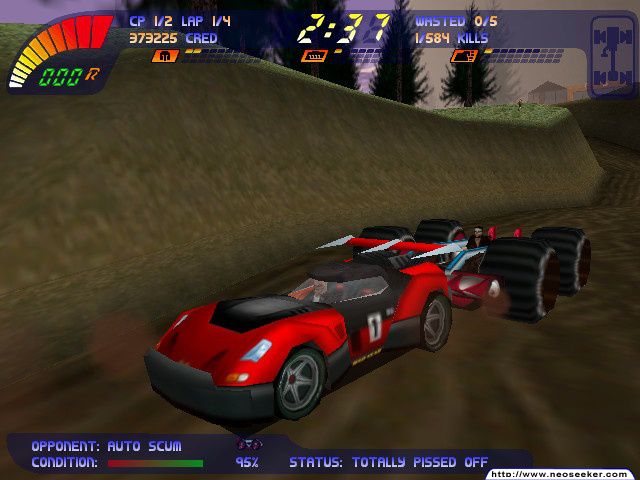

Use text to give brief insights into other characters’ mindsets outside of dialog. It’s mystifying why this isn’t used more. Classic games Carmageddon 2 and Operation: Inner Space both utilized this to great success. In both games, you compete in open-ended levels with multiple ways to achieve victory. In both games, you competed against crudely-rendered opponents, but one simple addition made them seem more alive than in any comparable current-gen game: brief text descriptions telling you what they were thinking.

When you shot at a neutral spaceship in Operation: Inner Space, you would see their description change from “Aimlessly wandering” to “Seething with fury” – and the payoff from this simple addition was immeasurable. Sharing their hypothetical ‘inner thoughts’ made an enormous difference in helping players visualize them inside their vehicles, making confrontations infinitely more exciting. Enemy ships and cars became fully-realized entities, making collections of AI routines and scripted behaviors seem like real enemies out for your blood.

Use character dynamism to prompt questions. In other words, have characters do unexpected things that make total sense, given the context. In Hotline Miami’s first level, after brutally slaying your first group of foes, your character unexpectedly drops to his knees and vomits in an alley. Was it the shock of killing a bunch of dudes? Was he on drugs? It’s never really explained, but this disquieting question prompts unanswered suspicions in the player’s mind that never really go away, which perfectly complements the game’s deranged atmosphere.

In Bioshock Infinite, when you explore Battleship Bay with Elizabeth after rescuing her, she marvels at all of the sights, trying to experience everything at once with several custom animation sequences. In the context of the game, this makes total sense – she’s a young woman who’s never been outside of her solitary tower, and naturally would want to poke her nose into anything that hinted of new. The small touches in this scene help endear her to the player, reinforcing both her curiosity of the outside world and her sad life up to this point as a captive.

Practice brevity in world-building. For most players, quality trumps quantity. Dishonored may have had a traditional linear story, but the world building was very well done. Throughout the game you would stumble upon short snippets of text – diary entries, poems, descriptions of far-off places – that helped the player paint a picture of Dunwall as one of many grim places in an equally grim world. The short messages scrawled in Left 4 Dead’s safe rooms are widely accepted as a prime example of efficient world-building, imparting lots of meaningful incidental information without the intrusion of a cutscene.

On the other hand, Bioshock Infinite gorged itself on this kind of world-building to excess. The game had plenty of incidental props and displays, but they were absolutely EVERYWHERE. At times, it felt less like a game and more like a walking tour of extravagant billboards and set pieces, diluting the player’s ability to discover elements of the world themselves. In this example, the designers had taken on simulation duties of the in-between moments for themselves, depriving the player of making these connections.

(If) Optimize the IPU, (Then) Create a Rabid Fanbase

While it’s a lower priority than refining core mechanics and working around technical limitations, giving thought to maximizing use of the IPU can have surprising dividends for the end user experience, not to mention saving development time and resources allocated to less effective systems and content.

If anything else, getting used to the concept of the IPU as a legitimate development resource can have enormous implications in creating games that play, react, and feel more meaningful than ever.